The entire essay is well worth reading and is findable online if you hunt about. Here are some of the best bits about Frankenstein (the book):

Like the proletariat, the monster is denied a name and an individuality. He is the Frankenstein monster; he belongs wholly to his creator (just as one can speak of 'a Ford worker'). Like the proletariat, he is a collective and artificial creature. He is not found in nature, but built. Frankenstein is a productive inventor-scientist...). Reunited and brought back to life in the monster are the limbs of those - the 'poor' - whom the breakdown of feudal relations has forced into brigandage, poverty and death. Only modern science - this metaphor for the 'dark satanic mills' - can offer them a future. It sews them together again, moulds them according to its will and finally gives them life, But at the moment the monster opens its eyes, its creator

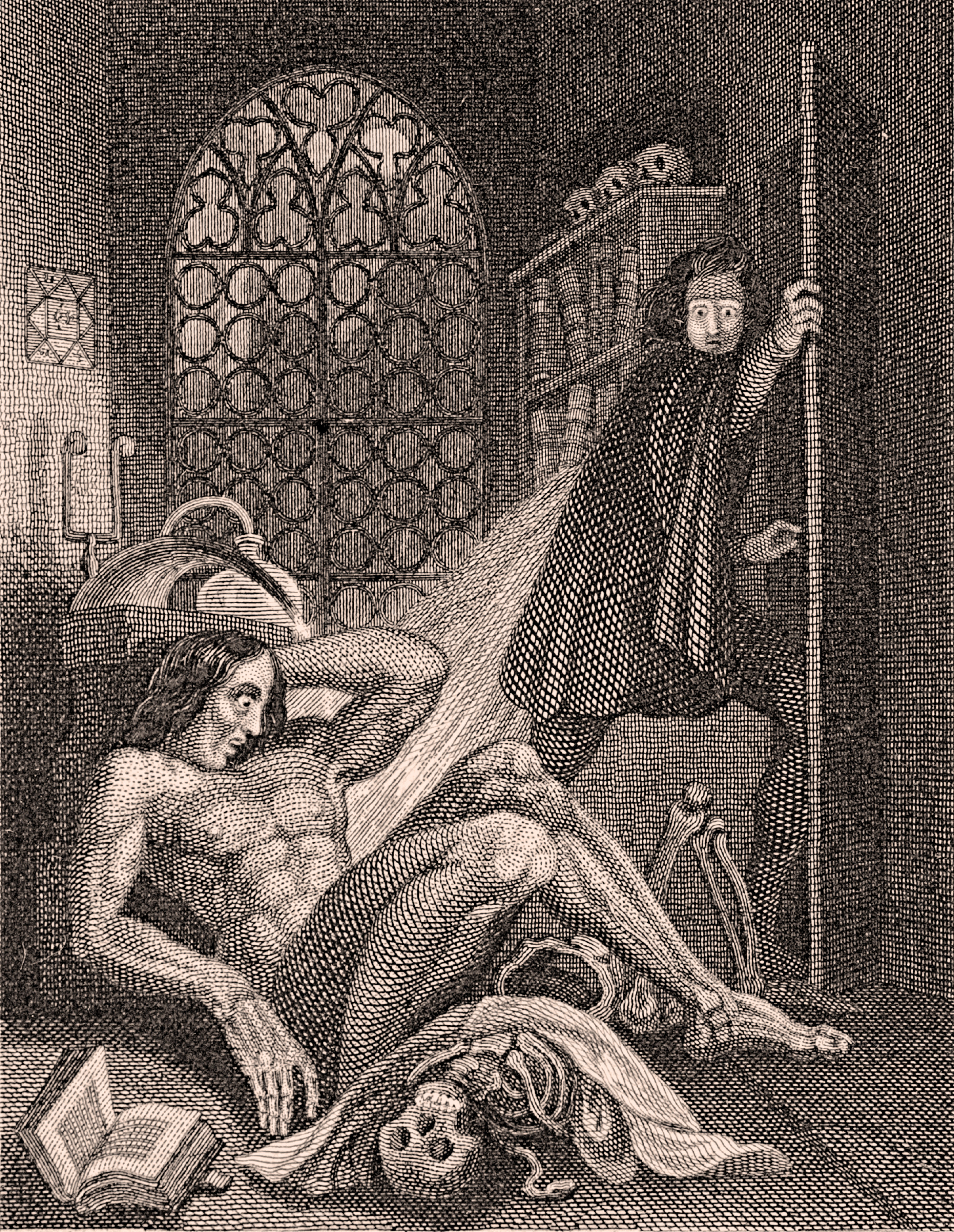

draws back in horror: 'by the glimmer of the half-extinguished light, I saw the dull yellow eye of the creature open; . . . How can I describe my emotions at this catastrophe . . . ?'

Between Frankenstein and the monster there is an ambivalent, dialectical relationship, the same as that which, according to Marx, connects capital with wage-labour. On the one hand, the scientist cannot but create the monster: 'often did my human nature turn with loathing from my occupation, whilst, still urged on by an eagerness which perpetually increased, I brought my work near to a conclusion'. On the other hand, he is immediately afraid of it and wants to kill it, because he realizes he has given life to a creature stronger than himself and of which he cannot henceforth be free. ... The fear aroused by the monster, in other words, is the fear of one who is afraid of having 'produced his own gravediggers'.

and...

'Race of devils': this image of the proletariat encapsulates one of the most reactionary elements in Mary Shelley's ideology. The monster is a historical product, an artificial being: but once transformed into a 'race' he re-enters the immutable realm of Nature. He can become the object of an instinctive, elemental hatred; and 'men' need this hatred to counterbalance the force unleashed by the monster. So true is this that racial discrimination is not superimposed on the development of the narrative but springs directly from it: it is not only Mary Shelley who wants to make the monster a creature of another race, but Frankenstein himself. Frankenstein does not in fact want to create a man (as he claims) but a monster, a race. He narrates at length the 'infinite pains and care' with which he had endeavoured to form the creature; he tells us that 'his limbs were in proportion' and that he had 'selected his features as beautiful'. So many lies -- in the same paragraph, three words later, we read: 'His yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath; his hair was of a lustrous black, and flowing; his teeth of a pearly whiteness; but these luxuriances only formed a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes. . . . his shrivelled complexion and straight black lips.' Even before he begins to live, this new being is already monstrous, already a race apart. He must be so, he is made to be so -- he is created but on these conditions. There is here a clear lament for the feudal sumptuary laws which, by imposing a particular style of dress on each social rank, allowed it to be recognized at a distance and nailed it physically to its social role. Now that clothes have become commodities that anyone can buy, this is no longer possible. Difference in rank must now be inscribed more deeply: in one's skin, one's eyes, one's build. The monster makes us realize how hard it was for the dominant classes to resign themselves to the idea that all human beings are - or ought to be - equal.

I have some issues with Moretti here. He uses the word 'lies' to describe Victor's supposedly inaccurate descriptions of the monster as beautiful. But, firstly, we are confusing perception with reality. Victor perceives his construction as beautiful because he attempts to construct it according to implicitly classical notions of beauty (note the key word "proportion", and remember that original woodcut which depicts the monster as a giganticised and jumbled reiteration of Michaelangelo's newly-created Adam)... but there is no guarantee that things that accord with classical notions of proportion will actually be beautiful. Rather, beauty is concept we have mapped onto certain stereotypical physicalities which stem from a bastardized and historically re-written version of classicism, recast in terms of 18th and 19th century bourgeois prejudices. It is profoundly local - historically, geographically, socially and ideologically. It is implicitly tied in with notions of 'health' which stem from the privileged lives of the rich (smooth skin, for example), and which later get appropriated by reductionist Darwinian ideologies which link beauty with 'fitness'... a set of notions still widely repeated by today's biological determinists. It would be perfectly possible to construct something according to abstract classical (or pseudo-classical) notions of beauty that turned out hideous and terrifying to the beholder. Just imagine actually meeting Michaelangelo's David in the street.

But this leads us to another issue. As stated, we're talking about Victor's perceptions. What seemed beautiful to him in conception, in theory, during construction, in isolated parts, could well seem ghastly in totality. Or perhaps the totality of the final creation simply brings home to Victor the ramifications of what he has done. He has created something which now has seperate existence, seperate power, autonomy and selfhood. When he looks at it as another person as opposed to a plan or a set of pieces to be assembled, he suddenly finds it frightening. This actually fits better with Moretti's conception of the monster as a proletariat in singular, as terrifying because the creator perceives it as his potential gravedigger. Like many creators of actual proletarian populations, Victor the bourgeois looks at what he has created and, in place of the vast reservoir of ready and eager and docile and easily-exploited labour that he planned, he sees something terrifyingly dangerous precisely because of its autonomy.

This in turn leads to another issue. In the preceding quoted paragraph, Moretti is talking about the bourgeois conception of the lower orders as hideously unequal or inferior. He implies a relation between this (which found itself expressed in Darwinian reductionist narratives about degraded 'types' or 'natural lower orders') and between the racial narrative of capitalism. But he seems to be flailing about for a psychological rationale for racism as a response to the horror of the subjected object. But the process of 'race making', in which the bourgeois social order constructs the ideology of biological race (and thus of biological racism) as a justification for racially-ordered systems of labour exploitation, i.e. slavery and the slave trade, is a fair bit more material than that. Furthermore, the psychological aspect (which is definitely present) is based not on horror at the subject but on the need to confront a living subject and make it an object that is horrifying, and thus subjectable. To turn workers who are black into 'negro slaves' for instance, from people who are being exploited into monsters who deserve no better. Moretti misses the extent to which race is ideologically constructed, and the extent to which it thus filters into perceptions. He puts it the wrong way round, or seems to. Having constructed the ideology of racial orders, the system then creates consciousness in people which causes them to perceive racial difference that is not, as we now know, actually existing in nature. There are no 'races', and we construct them out of ideology which acts upon our perceptions of ethnic variations. This, it seems to me, is actually directly mirrored in Victor's sudden perception of his new creation as ugly. He looks at it and called it beautiful, then looks again and perceives it as ugly - which is to say, as Moretti points out, as racially 'other'. And the only change is a material one. The creature is now alive. He made it ugly because it came alive and its disavowal needed an ideological justification. Victor, in effect, 'makes' a race in two senses. He runs the risk of creating a 'race of devils' in the sense of creating a new breed among humans. But this is the diegetic sense that he, the character, perceives and believes. Beneath that, there is Victor as a textual reification of ideological maneuvres. In that sense, what he's actually doing is 'race making'. He is superimposing an ideology of racial difference and hierarchy upon a 'wretch' that he deems inferior because it is both his slave and his potential gravedigger. Its status as a living thing makes this ideologically necessary. That other people perceive the monster in essentially the same way only speaks to the universality of the ideology of race once constructed.

Moretti goes on to recognise something of the instability of some of those aforementioned bourgeois conceptions of beauty, and to bring in the artificiality of race, in the following passage - which is also a neat demonstration of the Marxist insight that progress and barbarism are forever intertwined, to the extent that they are essentially the same thing:

But the monster also makes us realize that in an unequal society they are not equal. Not because they belong to different 'races' but because inequality really does score itself into one's skin, one's eyes and one's body. And more so, evidently, in the case of the first industrial workers: the monster is disfigured not only because Frankenstein wants him to be like that, but also because this was how things actually were in the first decades of the industrial revolution. In him, the metaphors of the critics of civil society become real. The monster incarnates the dialectic of estranged labour described by the young Marx: 'the more his product is shaped, the more misshapen the worker; the more civilized his object, the more barbarous the worker; the more powerful the work, the more powerless the worker; the more intelligent the work, the duller the worker and the more he becomes a slave of nature. . . . It is true that labour produces . . . palaces, but hovels for the worker. . . . It produces intelligence, but it produces idiocy and cretinism for the worker.' Frankenstein's invention is thus a pregnant metaphor of the process of capitalist production, which forms by deforming, civilizes by barbarizing, enriches by impoverishing -- a two-sided process in which each affirmation entails a negation. And indeed the monster - the pedestal on which Frankenstein erects his anguished greatness - is always described by negation: man is well proportioned, the monster is not; man is beautiful, the monster ugly; man is good, the monster evil. The monster is man turned upside-down, negated. He has no autonomous existence; he can never be really free or have a future. He lives only as the other side of that coin which is Frankenstein. When the scientist dies, the monster does not know what to do with his own life and commits suicide.

Mary Shelley became something of a reactionary in later life. Despite being a radical critique of the Enlightenment project and the dawning Industrial Revolution, Frankenstein is a book with more than a seed of the reactionary nestling within it. Like many from the early years of capitalism who disapproved of the new system in some measure, she is in many respects essentially a conservative. Shakespeare, writing at the very dawn of the Early Modern Era, at the fulcrum of the transition from fedualism to capitalism, is highly critical of many aspects of the emergent bourgeois culture (along with being irresistibly attracted to them) but his criticism takes the form of an essentially conservative attachment to pre-bourgeois ideas of social obligation. Capitalism detaches pre-capitalist people from old and established ties of obligation which constitute the social structure of fedualism. He sympathises with shepherds leading newly precarious lives in the Forest of Arden after the enclosures, but he also worries about the fickleness of the new urban proles (so like the vicious Roman mob!), and so on. Timon rages at money the universal whore, the utterly faithless golden metaphor which, in the bourgeois system, breaks down all loyalties and moral certainties... and yet Shakespeare's solution is for the classical virtues to be imposed by martial law in the person of Alcibiades. In the same way, Mary Shelley frets at the emergence of the new bourgeois product - so powerful, so autonomous - and the newly forming proletariat - so powerful, so autonomous - even as she rails at the failure of social justice contained within the new system. The book is a critique from a radical position but also from a privileged one. Shelley sees the ruthless failure of tolerance and compassion and social justice which is contained within these new phenomena. The Enlightenment project will fail if it is not cared for and nurtured, and justice is the most essential pre-requisite... and that justice is being denied. But, even as she rails at justice denied, she frets at the revenge of history. This is perfectly in line with the reservations of Mary's father, Godwin, who wants reform through fireside chats with the educated, and her radical boyfriend-later-husband, Percy Shelley, who flip-flops back-and-forth between foaming revolutionism and elitest worrying about the ignorant mob.

But, in some ways, Mary goes further. Frankenstein is almost a declaration that the entire project - not just reform but capitalism itself - is doomed to failure. This is not a categorical judgement. There are countervailing tendencies in this book and others she wrote. She was always profoundly ambivalent about Romanticism and the Enlightenment - something that makes her such a fascinating liminal figure in her milieu. But it seems that, for her, the monstrous nature of the products - be they machines or classes - dooms them to forever be denied justice and responsible use. Without the perspective of class struggle, she doesn't see the possibility that the new class could remake the world. She does, however, see 'the common ruination of the contending classes'. But she lived before capitalism had spread across the globe and taken over. To her, it's not too late for the world to go back to how it was before, once those warring opposites kill each other. Frankenstein and the monster destroy each other. They both die without issue. The 'race of devils' is never spawned. As Moretti points out, Frankenstein has no way of utilising the creature because capital is erased from the picture. There are no factories for it and its kin to work in. It is never cconceived of as productive, or as having utility. Mary Shelley turns the two men - and Capital and Labour - into a doomed fable.

These days, the end of the world is now proverbially known to be easier to imagine than the end of capitalism. To Mary Shelley, it was decidedly the other way round.

(Edited and slightly amended, 18/3/15.)